By Maung Zarni | Published by FORSEA on July 18, 2020

The painful but necessary question – How will or can Myanmar be de-constructed, or more alarmingly, disintegrated? – needs to be asked openly and debated publicly.

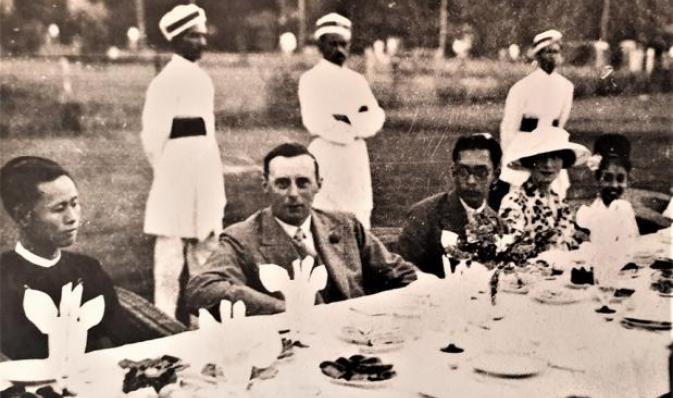

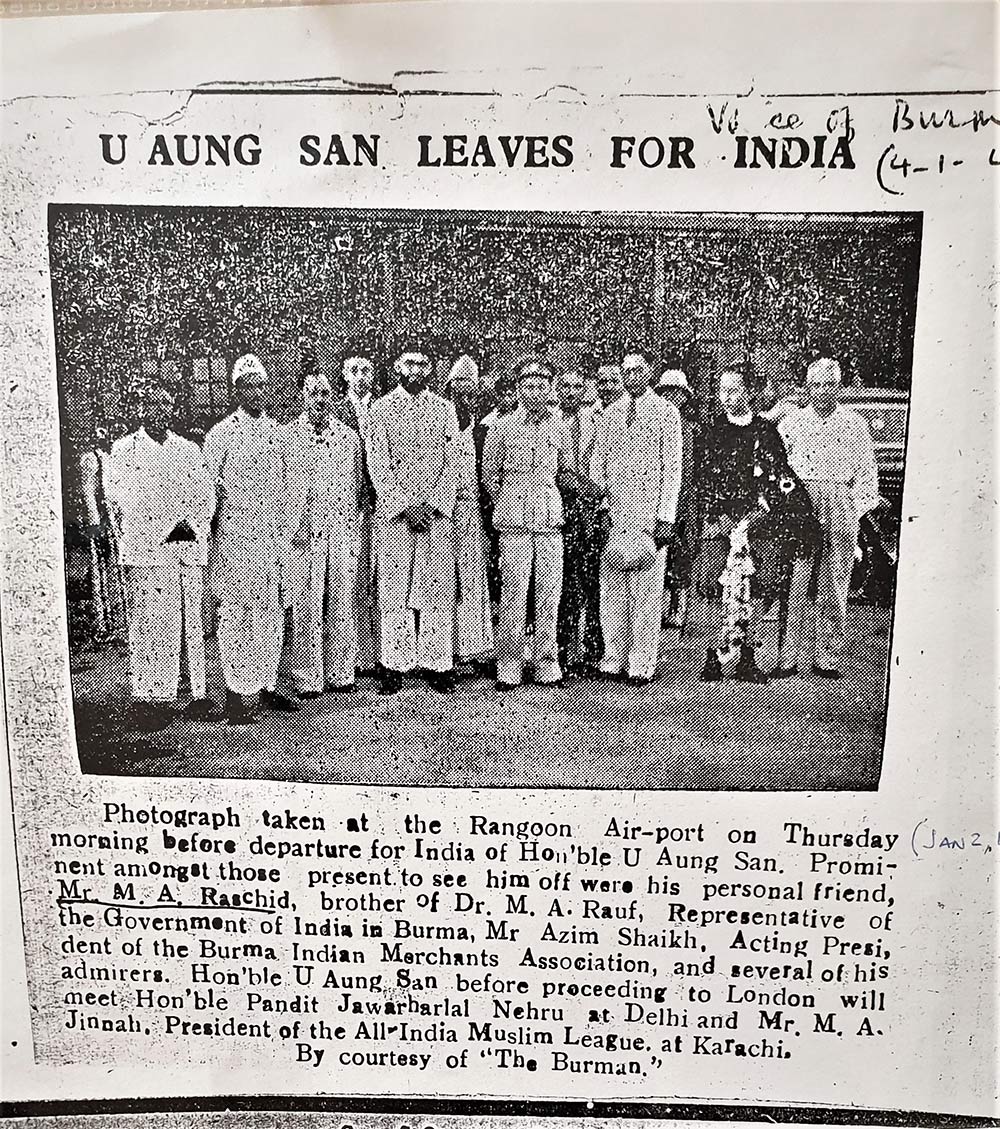

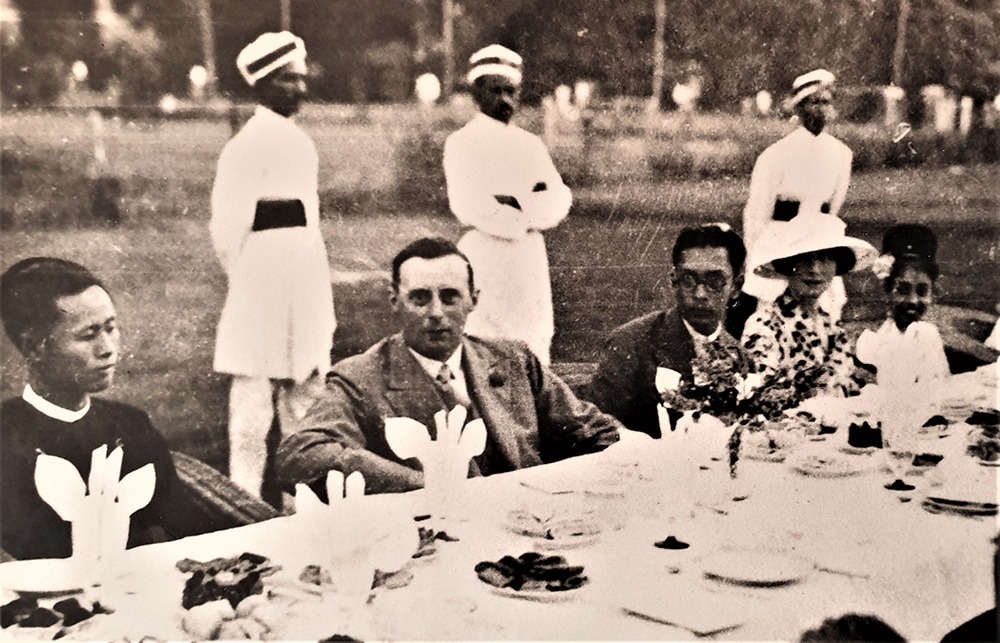

Sunday – July 19 – marks the 73rd anniversary of the assassination of U Aung San, the father of Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, and a group of his multi-ethnic colleagues in his pre-colonial cabinet, including the Muslim leader and educator Mr Razak from my hometown of Mandalay.

As the country prepares to commemorate its Martyrs Day, I begin to feel that these Burmese martyrs died in vain. After having studied my country’s politics, and been deeply involved in its affairs non-stop over the last 30 years, I am more than ever convinced of the need for anyone who cares about the country’s future to begin the project of de-imagining the failed polity that is Myanmar.

The painful but necessary question – How will or can Myanmar be de-constructed, or more alarmingly, disintegrated? – needs to be asked openly and debated publicly.

This project needs to be coupled with concurrent acts of reimagining new post-Myanmar as a mixture of independent nations and/or a cluster of federated autonomous states within a radically different Union of Burma. If we are to avoid the costly mistakes of the past 70 years, the new polities, whatever forms they take, will need to device civic regional, national and federal identities or citizenships, that are not anchored in the existing toxic ethno-nationalist identifies or mono-faith exclusionary identities.

In fact, Twan Mrat Naing, the revolutionary leader of the Arakan Army or AA and his armed resistance movement, have already launched publicly this twofold political project – namely de-imagining the completely failed state of Myanmar and reimagining a new Arakan autonomous or independent nation along the civic nationalist lines.

Judging by their core values statement and media interviews, Arakanese revolutionaries are already engaged in this project of dislodging the Burmese rule in Rakhine in both their popular imagination and on the ground. For the Burmese rule is something they have for 70 years experienced as a colonial administration. AA is openly attempting to build a new type of power structures, and revive the old consciousness of being a free and sovereign people, offering a broad inclusive non-primordial group identity which I have spelled out in the preceding paragraph – all without the fancy academic conceptualizations.

In the fall semester of 1994, I sat in on a graduate seminar by the late Benedict O.G. Anderson at Cornell University in New York where I was poring over the Burmese language materials held at the university’s Southeast Asia archives. I listened attentively to the brilliant theorist who created a new conceptual prism through which nation-states are now widely looked at: post-colonial nations as products of nationalist imagination, or in Anderson’s words, “imagined communities.”

A quarter century on and a few years after the famed academic’s passing in Bangkok, I feel the need to propose the antithesis of what my one-time teacher proposed: de-imagining a nation, that is, a nation that remains deeply colonial in its essence, in power structures and governing practices, and, equally important, a nation that shows absolutely no sign of self-reflection, let alone self-correction.

My own country of birth – Burma – is an ideal candidate ripe for de-imagining.

Against the background of brutal and bloody military crackdown of multi-ethnic and multi-class protest movement of 1988, the military rulers renamed the country as Myanmar. No plebiscite. No referendum. No opinion polls. No focus group discussions. Just like that in one day in 1989 in a move to whitewash its bloody rule of 26 years since 1962.

The incompetence of the military leadership was such that the lords in green uniform could not even device a name that was linguistically and phonemically correct. This blatant error was pointed out by the country’s eminent Burmese historian, the late Than Tun. “Myanmar” as the name of the country was, and remains, simply wrong in either in its transliteration of the Burmese word Myan Ma – note the correct spelling, without the strong ‘r’ at the end – or the usage of the word as a stand-alone proper name for the country.

It goes without saying that the linguistically challenged military leadership in their own mother-tongue, surely is bound to fail – and fail categorically – at nation-building, especially out of a patch work of largely agrarian multi-ethnic communities with mutually incomprehensible languages, and conflicting and competing historical memories.

A cursory glance at the state of the country

What a spectacular failure Myanmar has been since the martyrs’ assassination 73 years ago!

Under the two-tiered system of governance jointly and haphazardly run by U Aung San’s daughter and the Armed Forces which he founded under the fascist patronage of war-time Japan, the country is one of the world’s top five refugee-producers. In virtually all non-Burmese regions there are communities displaced by the fighting between the ethnically Burmese central government and minority armed resistance organizations. There are a total of over 20 ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), many of whom are engaged in the stalled peace-processes now led by Aung San Suu Kyi, using her favourite banner of Panglong or the old spirit of Union of Burma building which she considered her father’s gift to the nation.

But peace talks and ceasefire negotiations did not begin, not in the media-hyped heyday of the “Myanmar Spring” under the quasi-civilian regime of ex-general Thein Sein, but in the early 1960’s in the formative years of Ne Win’s dictatorship. For two consecutive generations, no peace agreements, written or gentlemanly consensus, has ever lasted. Bluntly put, peace is not even conceivable within the context of the military-controlled politics which blatantly cast aside all the agreed upon foundational principles of self-determination or ethnic equality, which are the prerequisite for the federated union of Burma or Myanmar, inclusive national identity, or the original political citizenship which rested on both residency and/or birth and ethnic indigeneity.

The coastal Rakhine state alone has become a frontline, playing host to estimated 200,000 war IDPs, primarily Rakhine Buddhists. This figure does not include the existing 120,000 – mainly Rohingya IDPs – herded and held in barbed wire camps in the wake of the two waves of mass violence in 2012. They are still there against their express wish to return to their places of residential origins in various towns in Rakhine, under the Naziesque “protective custody”, an old euphemism for the Jewish ghettos run by the SS. Their original neighbourhoods have been destroyed by Myanmar authorities to make way for the construction of deep-sea ports and other commercial projects.

The Burmese armed forces known as the Tatmadaw, and the generals’ cronies have been grabbing vast tracts of agricultural and forested land throughout the country.

Again in Rakhine state, the vast 60-k-stretch of area, both residential and agricultural, which once was home to 400 Rohingya villages – all destroyed in the genocidal purge of 740,000 Rohingyas in 2017 – was claimed officially by the civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi.

Since the most fertile agricultural land remains only in underlying regions of non-Burmese communities, the pervasive acts of land grab take on a racist colonial character. Land grab in these non-Burmese regions is not simply the class of ruling political, military and commercial elites, displacing ethnically Burmese peasants who also suffer class loot and landgrab. Thousands of displaced Burmese farmers who tilled the land are threatened with violence or legal action, or both, if they dare protest the loss of their only means of livelihoods.

A socialistic or even social democratic nation made up of different ethnic and faith-based communities as envisaged by the late founders of independent Burma, the country they left behind has not known peace since World War II. For the successive generations of the ethnically Burmese nationalists in power, politicians or generals, have attempted to impose their terms of peace and lopsided power arrangements with any non-dominant ethnic group, while disregarding the latter’s valid grievances including the unfettered extraction of above – and underground natural resources from the minority regions without a system of fair revenue or resource sharing with local and regional communities.

For my doctoral thesis on the Burmese nationalist politics, I interviewed the late Colonel Chit Myaing (retired in Virginia), a member of General Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council, in his home in Virginia in 1994.

He once served as a student bodyguard at the old colonial University of Rangoon to General Aung San and later joined the latter’s Burma Independence Army. He recounted the story of his regiment – Burma Rifle 5 – engaged in fierce battles against the bands of Arakanese liberation fighters on the front lines in Rakhine state on the very day the rest of the country was celebrating the transfer of sovereignty from the British rulers to the freshly minted nationalist government of the Union of Burma, after 120 years as a subjugated cluster of ethnic groups.

Not only is the independent state of new Burma born out of the World War II, but it was born into a long series of ethnicity-anchored wars.

For certain communities in the post-independent Burma, or Myanmar, World War II has not ended.

The architects of Burma’s independence including Suu Kyi’s father would be utterly appalled that in the Myanmar of 2020, the ruling hybrid government of Suu Kyi and the generals, would arrest and punish peace activists calling for the cessation of wars and military operations in minority regions and advocating peace and reconciliation, and they would be fined or thrown behind bars.

Besides, the world’s sole criminal court and the highest court to adjudicate inter-state legal disputes, namely International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice, are involved in Myanmar’s affairs. Both in the Hague, ICC has launched a full investigation into the violent criminal causes that triggered the exodus of nearly 1 million Rohingya people from Myanmar into Bangladesh in 2016 and 2017 while the ICJ is proceeding with the allegations of the genocide commissioned by Myanmar as a UN member state against Rohingya people, considered a protected group under the Genocide Convention.

Among the elite failures at nation-building are unceasing civil wars in different regions – albeit with varying degrees of intensity, chronic waves of exodus of refugees, IDPs in semi-concentration camps, permanent Karen refugee camps along Thai-Burmese borders, proliferation of ethnic armed organizations, with varying sizes and firepower, pervasive abject poverty, institutionalized corruption, which has become normative social practice, populist racist authoritarianisms and autocratic leaders who bark democracy.

Throughout history, old nations and empires self-destruct or are destroyed by external actors or factor. State power changes hand and maps are redrawn, perhaps not as often as we change our clothes; but, nonetheless unexpected and large-scale changes do take place. The League of Nations, the Weimer Republic or the Third Reich, the Berlin Wall and the GDR, the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, British and Ottoman empires, French-Indochina, and Yugoslavia spring to mind.

At this juncture in Myanmar’s political history it is difficult to conceive of how Myanmar too will succumb to the law of Impermanence. However, in Myanmar under the firm grip of the military, there are signs of a Burmese way to Balkanization. Nations come and go under the powerful external factors and forces – such as wars, or radical shift in geopolitical alignments, economic catastrophes, or internal revolutions.

De-Imagining Myanmar

I think the Arakan Army and its leadership have already unleashed Myanmar’s balkanization, that is, de-imaging and dismantling of the existing repressive polity and reimagining a new type of politics.

In the 1990’s as an overseas student activist possessed by anti-dictatorship passions informed by majoritarian patriotic sentiments, I rooted for Aung San Suu Kyi as she promised a democratic and ethnically reconciled Burma. Most Burmese are convinced that she is the best the country has had since her father’s assassination, and many continue to pin hopes on her – that she will try to put the country on the path towards democracy and development.

Suu Kyi may be the best that has happened to the Burmese Buddhist majority since independence. But she has proven not good or capable enough to re-steer the country on the multiculturalist social democratic path that the founders of post-independence Burma or Myanmar gave up their lives, youth, and careers for.

Suu Kyi’s Big Sister mistreatment of non-dominant ethnic communities and their representatives, her attempt to erect her martyred father in ethnic regions where he is not seen as their liberator or leader, her hopeless coddling of the Burmese generals whom she calls “my father’s sons”, and her autocratic civilian rule, sprinkled with flowery words of electoral democracy prove that she is just the civilian version of her cruder, and more brutish partners in genocidal and colonial crimes – the Burmese military leaders.

Against this backdrop, I’d say an unequivocal YES to the new, if highly provocative project of de-imagining Myanmar as the system no longer serves to protect or promote the interests and welfare of its inhabitants, majority or minorities.

Dr Maung Zarni is a scholar, educator and human rights activist with 30-years of involvement in Burmese political affairs, Zarni has been denounced as an “enemy of the State” for his opposition to the Myanmar genocide. He is the co-author (with Natalie Brinham) of the pioneering study, "The Slow Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingyas" (Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal, Spring 2014) and "Reworking the Colonial-Era Indian Peril: Myanmar’s State-Directed Persecution of Rohingyas and Other Muslims" (The Brown Journal of World Affairs, Fall/Winter 2017/18).