Numbers speak volume: in 1978, 280,000 (in 4 months); in 1991-92, 260,000; in 2012 (130,000 IDP + 100,000 boat people)

The framing has changed since the army's concerns about the cross-border migration of a people whose presence in the region predates drawing of post-WWII boundaries between then East Pakistan and the Union of Burma in the 1950's and 1960's.

By 1978, the military adopted a radical strategy of draining Southern and Middle part of the old Arakan region - renamed Rakhine - of Rohingyas.

But the threat of the military regime of the newly independent Bangladesh (since 1971) to arm 280,000 Rohingya refugees on Bangladeshi soil forced the Burmese military's hand: over 230,000 were taken back via UNHCR assisted repatriation program.

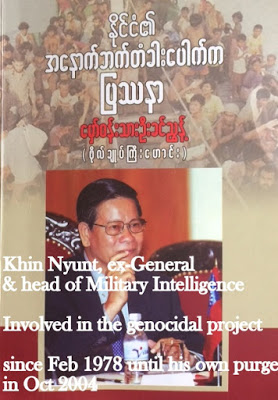

By 1991, the military stepped up its anti-Rohingya project and founded an inter-agency tool for persecution - Na Sa Ka (or border affairs unit) with the then Chief of Military Intelligence Gen. Khin Nyunt as its head. And a new exodus of over 260,000 ensued as the result of the new persecution.

By 2012, the persecution was outsourced to the local Rakhine nationalists, who were increasingly vocal about their demands for fair-revenue sharing and greater political autonomy from the Burmese-controlled central government. Rakhines dropped their demands and gave into their powerful racist instincts to beat up the weak, rather than confront the powerful colonizer - the Burmese military. (The Burmese feudal court destroyed multi-ethnic coastal Arakan kingdom of Buddhist Rakhine kings on 1 January 1785).

The Myanmar Gov, with the help of media and external players such as the ICG cleverly framed the state-directed persecution as "communal or sectarian conflict", primarily, thus absolving the state of its primary role in it.

By 2016, the government allowed a small desperate gang of Rohingya youth to attack its border posts - nothing happened in the Rohingya communities, without the knowledge of the intelligence as the Rohingyas' physical movements are severely restricted and closely monitored - and pounced on the entire Rohingya region in N. Arakan, framing the lured attackers as "Muslim insurgents" "Jihadists" "terrorists", etc.

Myanmar Generals sacrifices routinely thousands of Burmese rank and file soldiers in East and Nothern Burma's battles with Kachin, Shan, Kokant, etc. Loss of 9 soldiers in 3 separate if coordinated attacks by sword-wielding Rohingya "militants" is not even an issue worthy of War Office discussion.

This evolutionary pattern of persecution - with the sole intent of destroying the Rohingyas - its identity, its history, its material foundations, its cultural foundations, its literal existence - is what i consider unequivocally a full-fledged GENOCIDE.

Hitler only had less than 15 years to pursue his inhuman projects: but the Burmese military has all the time in its hands. For the world sits on its hand - since the first exodus of Rohingyas - numbering nearly 280,000 fled (by ex-General Khin Nyunt's own admissions) in 4 months in 1978 (12 Feb 1978 till June, with the month of May as a lull).

ZARNI

========================================

65,000 Rohingya flee from Myanmar to Bangladesh following crackdown: UN

=========================================

The Rohingya Are Ready to Talk About the Atrocities in Burma

But they need the help of the international community, not only Muslim countries, if they are to be heard.

By PUTTANEE KANGKUN

Jan. 9, 2017 12:34 p.m. ET

Wall Street Journal

My colleagues and I recently spent nearly two weeks on the Burma-Bangladesh border interviewing dozens of Rohingya men and women who fled Maungdaw Township in Burma’s Rakhine State. The abuses they suffered at the hands of the Burmese military rise to the level of atrocity crimes. They require an urgent international response.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-rohingya-are-ready-to-talk-about-the-atrocities-in-burma-1483983264

========================================

‘There Are No Homes Left’: Rohingya Tell of Rape, Fire and Death in Myanmar

By ELLEN BARRYJAN. 10, 2017

New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/world/asia/rohingya-violence-myanmar.html

Rohingya from Myanmar at a refugee camp in Teknaf, Bangladesh, in December. An estimated 65,000 Rohingya have fled across the border, according to the International Organization for Migration. Credit A.M. Ahad/Associated Press

KUTUPALONG CAMP, Bangladesh — When the Myanmar military closed in on the village of Pwint Phyu Chaung, everyone had a few seconds to make a choice.

Noor Ankis, 25, chose to remain in her house, where she was told to kneel to be beaten, she said, until soldiers led her to the place where women were raped. Rashida Begum, 22, chose to plunge with her three children into a deep, swift-running creek, only to watch as her baby daughter slipped from her grasp.

Sufayat Ullah, 20, also chose the creek. He stayed in the water for two days and finally emerged to find that soldiers had set his family home on fire, leaving his mother, father and two brothers to asphyxiate inside.

These accounts and others, given over the last few days by refugees who fled Myanmar and are now living in Bangladesh, shed light on the violence that has unfolded in Myanmar in recent months as security forces there carry out a brutal counterinsurgencycampaign.

Their stories, though impossible to confirm independently, generally align with reports by human rights organizations that the military entered villages in northern Rakhine State shooting at random, set houses on fire with rocket launchers, and systematically raped girls and women. At least 1,500 homes were razed, according to an analysis of satellite images by Human Rights Watch.

The campaign, which has moved south in recent weeks, seems likely to continue until Myanmar’s government is satisfied that it has fully disarmed the militancy that has arisen among the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic group that has been persecuted for decades in majority-Buddhist Myanmar.

A total of 22,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar in the first two weeks of January in response to reported military violence.By SHANE O’NEILL on Publish Date January 10, 2017. . Watch in Times Video »

“There is a risk that we haven’t seen the worst of this yet,” said Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights, a nongovernmental organization focusing on human rights in Southeast Asia. “We’re not sure what the state security forces will do next, but we do know attacks on civilians are continuing.”

A commission appointed by Myanmar’s government last week denied allegations that its military was committing genocide in the villages, which have been closed to Western journalists and human rights investigators. Officials have said Rohingya forces are setting fire to their own houses and have denied most charges of human rights abuses, with the exception of a beating that was captured on video. Myanmar’s leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize, has been criticized for failing to respond more forcefully to the violence.

The crackdown began after an attack on three border posts in Rakhine State in October, in which nine police officers were killed. The attack is believed to have been carried out by an until-then-unknown armed Rohingya insurgent group.

The military campaign, which the government describes as a “clearing” operation, has largely targeted civilians, human rights groups say. It has sent an estimated 65,000 Rohingya fleeing across the border to Bangladesh, according to the International Organization for Migration.

“They started coming in like the tide,” said Dudu Miah, a Rohingya refugee who is chairman of the management committee at the Leda refugee camp, near the border with Myanmar. “They were acting crazy. They were a mess. They were saying, ‘They’ve killed my father, they’ve killed my mother, they’ve beaten me up.’ They were in disarray.”

Soldiers were attacking villages just across the Naf River, which separates Myanmar from Bangladesh, so close that Bangladeshis could see columns of smoke rise from burning villages on the other side, said Nazir Ahmed, the imam of a mosque that caters to Rohingyas

A destroyed house near Maungdaw in Rakhine State. At least 1,500 homes have been razed, according to Human Rights Watch.Credit Nyien Chan Naing/European Pressphoto Agency

He said it was true that some Rohingya, enraged by years of mistreatment by Myanmar forces, had organized themselves into a crude militant force, but that Myanmar had dramatically exaggerated its proportions and seriousness.

Rohingyas are “frustrated, and they are picking up sticks and making a call to defend themselves,” he said. “Now, if they find a farmer who has a machete at home, they say, ‘You are engaged in terrorism.’”

An analysis released last month by the International Crisis Group took a serious view of the new militant group, which it says is financed and organized by Rohingya émigrés in Saudi Arabia. Further violence, it warned, could accelerate radicalization among the Rohingya, who could become willing instruments of transnational jihadist groups.

In interviews in and around the Kutupalong and Leda refugee camps here, Rohingya who fled Myanmar in recent weeks said that military personnel initially went house to house seeking adult men, and then proceeded to rape women and burn homes. Many new arrivals are from Kyet Yoepin, a village where 245 buildings were destroyed during a two-day sweep in mid-October, according to Human Rights Watch.

Muhammad Shafiq, who is in his mid-20s, said he was at home with his family when he heard gunfire. Soldiers in camouflage banged on the door, then shot at it, he said. When he let them in, he said, “they took the women away, and lined up the men.”

Mr. Shafiq said that when a soldier grabbed his sister’s hand, he lunged at him, fearful the soldier intended to rape her, and was beaten so severely that the soldiers left him for dead. Later, he bolted with one of his children and was grazed by a soldier’s bullet on his elbow. He crawled for an hour on his hands and knees through a rice field, then watched, from a safe vantage point, as troops set fire to what remained of Kyet Yoepin.

Bangladeshi border guards at a common transit point for the Rohingya on the banks of the Naf River, which separates Myanmar from Bangladesh. Credit A.M. Ahad/Associated Press

“There are no homes left,” he said. “Everything is burned.”Jannatul Mawa, 25, who is from the same village, said she crawled toward the next village overnight, passing the shadowy forms of dead and wounded neighbors.

“Some were shot, some were killed with a blade,” she said. “Wherever they could find people, they were killing them.”

Dozens more families are from Pwint Phyu Chaung, which was near the site of a clash between militants and soldiers on Nov. 12.

According to Amnesty International, the militants scattered into neighboring villages. When army troops followed them, several hundred men from Pwint Phyu Chaung resisted, using crude weapons like farm implements and knives, the report said. A Myanmar army lieutenant colonel was shot dead, and the troops called in air support from two attack helicopters.

Mumtaz Begum, 40, said she was awakened at dawn when security forces approached the village from both sides and began searching for adult men in each house.

She said she and her daughter were told to kneel down outside their home with their hands over their heads and were beaten with bamboo clubs.

“There are no homes left,” he said. “Everything is burned.”

Jannatul Mawa, 25, who is from the same village, said she crawled toward the next village overnight, passing the shadowy forms of dead and wounded neighbors.

“Some were shot, some were killed with a blade,” she said. “Wherever they could find people, they were killing them.

Dozens more families are from Pwint Phyu Chaung, which was near the site of a clash between militants and soldiers on Nov. 12.

According to Amnesty International, the militants scattered into neighboring villages. When army troops followed them, several hundred men from Pwint Phyu Chaung resisted, using crude weapons like farm implements and knives, the report said. A Myanmar army lieutenant colonel was shot dead, and the troops called in air support from two attack helicopters.

Mumtaz Begum, 40, said she was awakened at dawn when security forces approached the village from both sides and began searching for adult men in each house.

She said she and her daughter were told to kneel down outside their home with their hands over their heads and were beaten with bamboo clubs.

Mumtaz Begum, 40, told of members of her family who were arrested, beaten, shot in the leg or killed. Her daughter described being grouped with young women to be raped. Credit Ellen Barry/The New York Times

She said her 10-year-old son was shot through the leg, her daughter’s husband was arrested, and her own husband was one of dozens of men and boys in the village who were killed by soldiers armed with guns or machetes that night. Villagers, she said, “laid the bodies down in a line in the mosque and counted them.”

Ms. Begum’s daughter, Noor Ankis, 25, said the next morning soldiers went from house to house looking for young women.

“They grouped the women together and brought them to one place,” she said. “The ones they liked they raped. It was just the girls and the military, no one else was there.”

She said the idea of trying to escape flickered through her head, but she was overcome by fatalism. “I felt there was no point in being alive,” she said.

Ms. Ankis pulled her head scarf low, for a moment, removing a tear. She said she had been thinking about her husband.

“I think about how he took care of me after we got married,” she said. “How will I see him again?”

Sufayat Ullah, 20, a madrasa student, said that he was home with his family on the morning of the attack and that the first thing he registered was the sound of gunfire. He realized quickly, he said, that he could only survive by escaping. “When they found people close by, they attacked them with machetes,” he said. “If they were far away, they shot them.”

Mr. Ullah ran from the house and bolted for the creek at the edge of town, and he dived in, swimming as far as he could. He said he spent much of the next two days underwater, finally scrambling onto the bank near a neighboring village. Only then did he learn that his mother, father and two brothers had burned to death inside the family house.

“I feel no peace,” he said, covering his face with his hands and weeping. “They killed my father and mother. What is left for me in this world?”

Maher Sattar contributed reporting.